1.1 Introduction

1.2 What is an Operating System?

An operating system (OS) is a resource manager.

It takes the form of a set of software routines that allow users and application

programs to access system resources (e.g.the CPU, memory, disks, modems, printers

network cards etc.) in a safe, efficient and abstract way.

For example, an OS ensures safe access

to a printer by allowing only one application program to send data directly

to the printer at any one time. An OS encourages efficient use

of the CPU by suspending programs that are waiting for I/O operations to

complete to make way for programs that can use the CPU more productively.

An OS also provides convenient

abstractions (such as files rather than disk locations) which isolate

application programmers and users from the details of the underlying hardware.

Fig. 1.1: General operating system architecture

Fig. 1.1 presents the architecture of a typical operating

system and shows how an OS succeeds in presenting users and application

programs with a uniform interface without regard to the details of the

underlying hardware.

We see that:

-

The operating system kernel

is in direct control of the underlying hardware. The kernel provides low-level

device, memory and processor management functions (e.g. dealing with interrupts

from hardware devices, sharing the processor among multiple programs, allocating

memory for programs etc.)

-

Basic hardware-independent kernel services are exposed to

higher-level programs through a library of system

calls (e.g. services to create a file,

begin execution of a program, or open a logical network connection to another

computer).

-

Application programs (e.g. word processors, spreadsheets) and

system utility programs (simple but useful application

programs that come with the operating system, e.g. programs which find

text inside a group of files) make use of system calls. Applications and

system utilities are launched using a shell

(a textual command line interface) or a graphical

user interface that provides direct user

interaction.

Operating systems (and different flavours of the same operating

system) can be distinguished from one another by the system calls, system

utilities and user interface they provide, as well as by the resource scheduling

policies implemented by the kernel.

1.3 A Brief History of UNIX

UNIX has been a popular OS for more than two

decades because of its multi-user, multi-tasking environment, stability,

portability and powerful networking capabilities. What follows here is

a simplified history of how UNIX has developed (to get an idea for how

complicated things really are, see the web site

http://www.levenez.com/unix/).

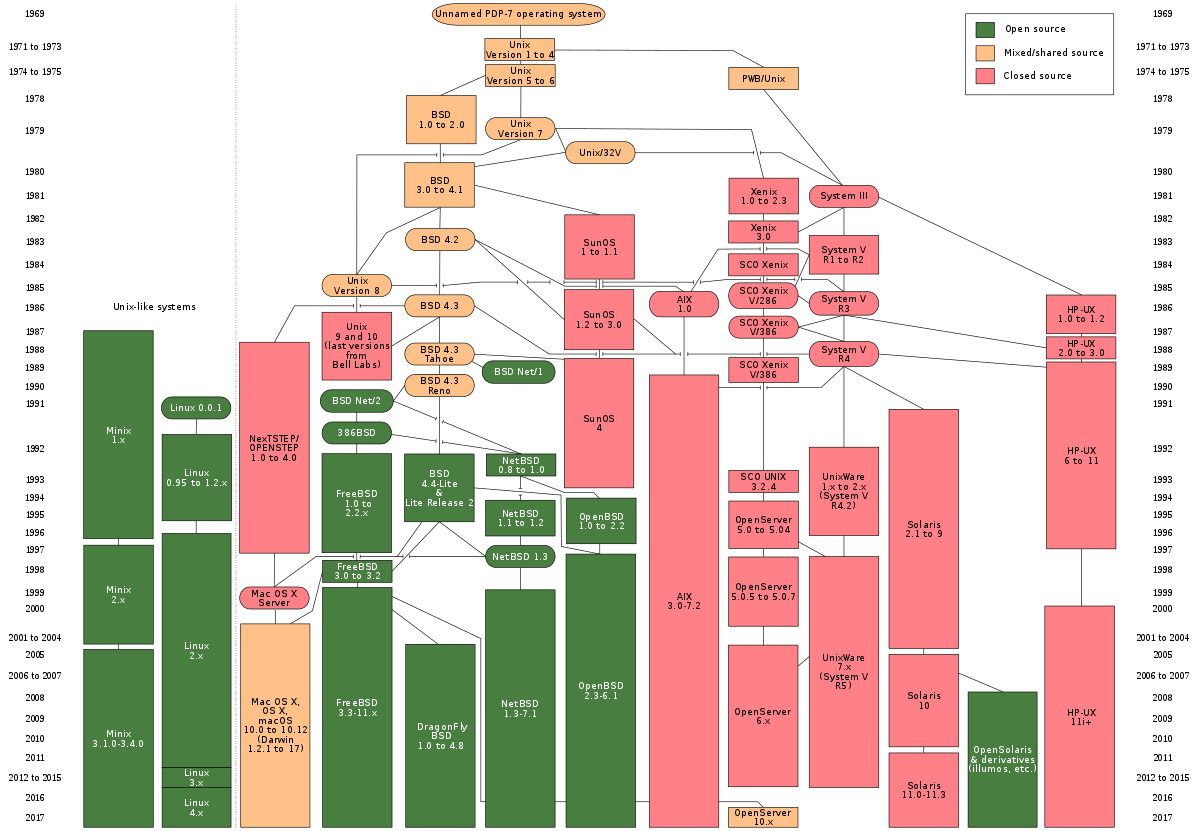

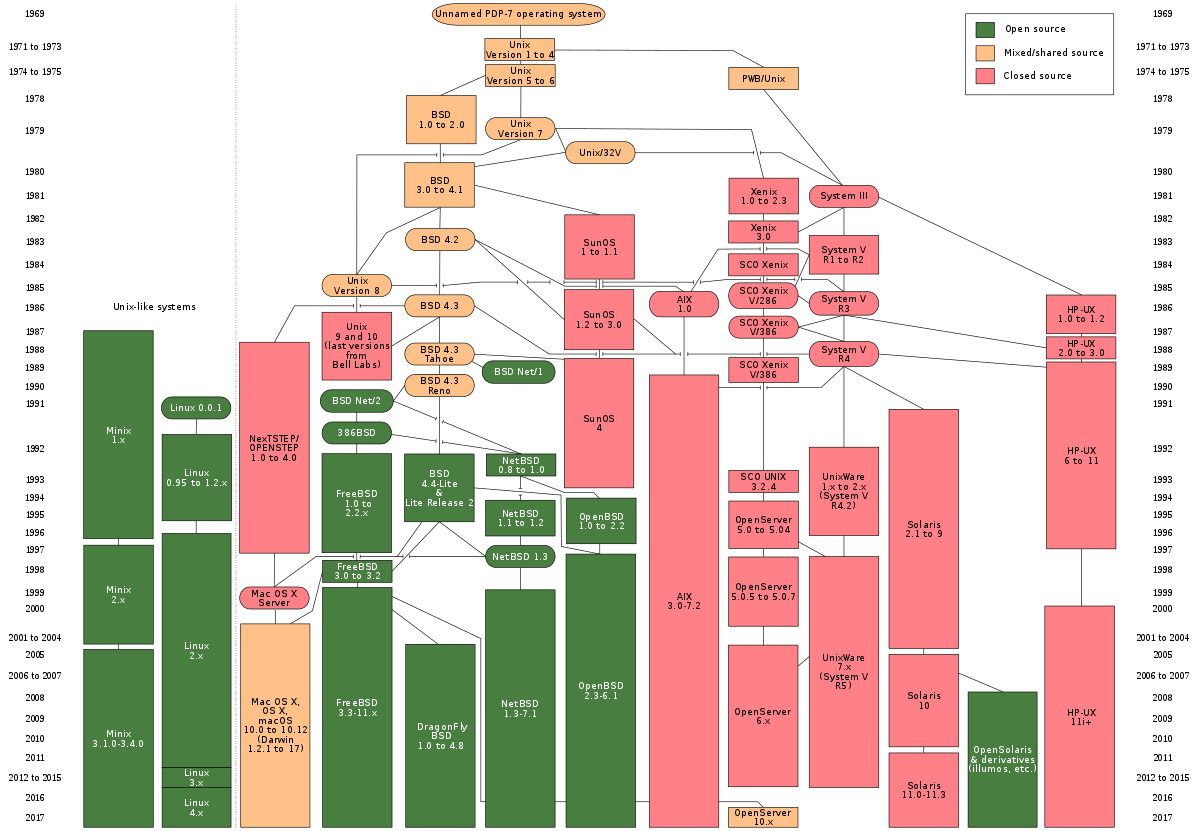

Fig. 1.2: UNIX FamilyTree

In the late 1960s, researchers from General Electric,

MIT and Bell Labs launched a joint project to develop an ambitious multi-user,

multi-tasking OS for mainframe computers known as MULTICS (Multiplexed

Information and Computing System). MULTICS failed (for

some MULTICS enthusiasts "failed" is perhaps too

strong a word to use here), but it did inspire Ken

Thompson, who was a researcher at Bell Labs, to have a go at writing a

simpler operating system himself. He wrote a simpler version of MULTICS

on a PDP7 in assembler and called his attempt UNICS (Uniplexed Information

and Computing System). Because memory and CPU power were at a premium in

those days, UNICS (eventually shortened to UNIX) used short commands to

minimize the space needed to store them and the time needed to decode them

- hence the tradition of short UNIX commands we use today, e.g. ls,

cp, rm, mv etc.

Ken Thompson then teamed up with Dennis Ritchie, the author

of the first C compiler in 1973. They rewrote the UNIX kernel in C - this

was a big step forwards in terms of the system's portability - and released

the Fifth Edition of UNIX to universities in 1974. The Seventh Edition,

released in 1978, marked a split in UNIX development into two main branches:

SYSV (System 5) and BSD (Berkeley Software Distribution). BSD arose from

the University of California at Berkeley where Ken Thompson spent a sabbatical

year. Its development was continued by students at Berkeley and other research

institutions. SYSV was developed by AT&T and other commercial companies.

UNIX flavours based on SYSV have traditionally been more conservative,

but better supported than BSD-based flavours.

The latest incarnations of SYSV (SVR4 or System 5 Release

4) and BSD Unix are actually very similar. Some minor differences are to

be found in; file system structure, system utility names and options

and system call libraries as shown in Fig 1.3.

| Feature |

Typical SYSV |

Typical BSD |

| kernel name |

/unix |

/vmunix |

| boot init |

/etc/rc.d directories |

/etc/rc.* files |

| mounted FS |

/etc/mnttab |

/etc/mtab |

| default shell |

sh, ksh |

csh, tcsh |

| FS block size |

512 bytes -> 2k |

4k -> 8k |

| print subsystem |

lp, lpstat, cancel |

lpr, lpq, lprm |

| echo command (no new line) |

echo "\c" |

echo -n |

| ps command |

ps -fae |

ps -aux |

| multiple wait syscalls |

poll |

select |

| memory access syscalls |

memset, memcpy |

bzero, bcopy |

Fig. 1.3: Differences between SYSV and BSD

GNU/Linux is a free open source UNIX OS which was created in 1991 by Linus Torvalds,

a Finnish undergraduate student. In reality, GNU/Linux is a combination of

the kernel, developed Torvalds, and software developed by the

Free Software Foundation's - GNU Project

which provided compilers, editors, libraries, system ultilties.

Although it is more accurate to refer to Linux as GNU/Linux, today most refer to

GNU/Linux as simply Linux.

Fig. 1.4: GNU/Linux

Linux is neither pure SYSV or pure BSD. Instead, incorporates some features from

each (e.g. SYSV-style startup files but BSD-style file system layout) and

aims to conform with a set of IEEE standards called POSIX (Portable Operating

System Interface). To maximise code portability, it typically supports

SYSV, BSD and POSIX system calls (e.g.

poll, select, memset, memcpy,

bzero and bcopy are all supported).

The open source nature of Linux means that the source

code for the Linux kernel is freely available so that anyone can add features

and correct deficiencies. This approach has been very successful and what

started as one person's project has now turned into a collaboration of

hundreds of volunteer developers from around the globe. The open source

approach has not just successfully been applied to kernel code, but also

to application programs for Linux.

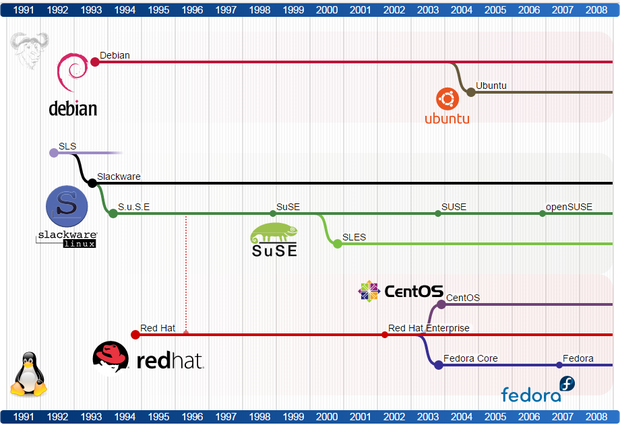

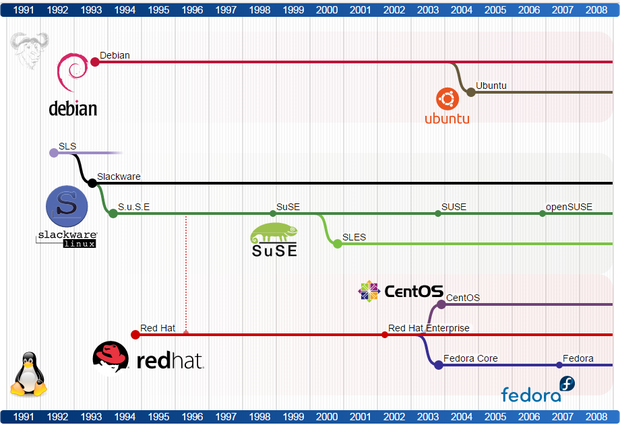

As Linux has become more popular, several different development

streams or distributions have emerged, e.g. Redhat, Slackware,

Debian, and Ubuntu. A distribution comprises a prepackaged kernel, system

utilities, GUI interfaces and application programs.

Fig. 1.4: Linux Distributions

1.4 Architecture of the Linux Operating System

Linux has all of the components of a typical OS:

- Kernel

The Linux kernel includes device driver support for a large number of PC hardware

devices (graphics cards, network cards, hard

disks etc.), advanced processor and memory management features, and support

for many different types of filesystems. In terms of the services that it provides

to application programs and system utilities, the kernel implements most

BSD and SYSV system calls, as well as the system calls described in the

POSIX.1 specification.

The kernel (in raw binary form that is loaded directly

into memory at system startup time) is typically found in the file /boot/vmlinuz,

while the source files can usually be found in /usr/src/linux.The latest

version of the Linux kernel sources can be downloaded from http://www.kernel.org.

- Shells and GUIs

Linux supports two forms of command input: through textual

command line shells similar to those found on most UNIX systems (e.g. sh

- the Bourne shell, bash - the Bourne again shell and csh - the C shell)

and through graphical interfaces (GUIs) such as the KDE and GNOME window

managers. If you are connecting remotely to a server your access will typically

be through a command line shell.

- System Utilities

Virtually every system utility that you would expect

to find on standard implementations of UNIX (including every system utility

described in the POSIX.2 specification) has been ported to Linux. This

includes commands such as ls, cp, grep, awk, sed, bc, wc, more,

and so on. These system utilities are designed to be powerful tools that

do a single task extremely well (e.g. grep finds text inside files

while wc counts the number of words, lines and bytes inside a

file). Users can often solve problems by interconnecting these tools instead

of writing a large monolithic application program.

Like other UNIX flavours, Linux's system utilities also

include server programs called daemons

which provide remote network and administration services (e.g. telnetd

and sshd provide remote login facilities, lpd provides

printing services,

httpd serves web pages, crond runs

regular system administration tasks automatically). A daemon (probably

derived from the Latin word which refers to a beneficient spirit who watches

over someone, or perhaps short for "Disk And Execution MONitor") is usually

spawned automatically at system startup and spends most of its time lying

dormant (lurking?) waiting for some event to occur.

- Application programs

Linux distributions typically come with several useful

application programs as standard. Examples include the emacs editor,

xv

(an image viewer), gcc (a C compiler), g++ (a C++ compiler),

xfig

(a drawing package), latex (a powerful typesetting language) and

soffice

(StarOffice, which is an MS-Office style clone that can read and write

Word, Excel and PowerPoint files).

Debian Linux also comes with apt,

Advanced Package Tool which makes it easy to install and uninstall application

programs.

1.5 Logging into (and out of) UNIX Systems

Text-based (TTY) terminals:

When you connect to a UNIX computer remotely (using ssh)

or when you log in locally using a text-only terminal, you will see the

prompt:

login:

At this prompt, type in your usename and press the enter/return/

key. Remember that UNIX is case sensitive (i.e. Will, WILL and will are

all different logins). You should then be prompted for your password:

login: will

password:

Type your password in at the prompt and press the enter/return/

key. Note that your password will not be displayed on the screen as you

type it in.

If you mistype your username or password you will get

an appropriate message from the computer and you will be presented with

the login: prompt again. Otherwise you should be presented with

a shell prompt which looks something like this:

$

To log out of a text-based UNIX shell, type "exit" at

the shell prompt (or if that doesn't work try "logout"; if that doesn't

work press ctrl-d).

Graphical terminals:

If you're logging into a UNIX computer locally, or if

you are using a remote login facility that supports graphics, you might

instead be presented with a graphical prompt with login and password fields.

Enter your user name and password in the same way as above (N.B. you may

need to press the TAB key to move between fields).

Once you are logged in, you should be presented with a

graphical window manager.

To bring up a window containing a shell prompt look for menus or icons

which mention the words "shell", "xterm", "console" or "terminal emulator".

To log out of a graphical window manager, look for menu

options similar to "Log out" or "Exit".

1.6 Changing your password

One of the things you should do when you log

in for the first time is to change your password.

The UNIX command to change your password is passwd:

$ passwd

The system will prompt you for your old password, then

for your new password. To eliminate any possible typing errors you have

made in your new password, it will ask you to reconfirm your new password.

Remember the following points when choosing your password:

-

Avoid characters which might not appear on all keyboards,

e.g. '£'.

-

The weakest link in most computer security is user passwords

so keep your password a secret, don't write it down and don't tell it to

anyone else. Also avoid dictionary words or words related to your personal

details (e.g. your boyfriend or girlfriend's name or your login).

-

Make it at least 7 or 8 characters long and try to use a

mix of letters, numbers and punctuation.

1.7 General format of UNIX commands

A UNIX command line consists of the name of a

UNIX command (actually the "command" is the name of a built-in shell command,

a system utility or an application program) followed by its "arguments"

(options and the target filenames and/or expressions). The general syntax

for a UNIX command is

$ command -options targets

Here command can be though of as a verb, options

as an adverb and targets as the direct objects of the verb. In the

case that the user wishes to specify several options, these need not always

be listed separately (the options can sometimes be listed altogether after

a single dash).

(Contents)